Storage Reliability Calculations

02 December 2016

When designing storage systems, for example comparing different coding schema, it is necessary to calculate reliability numbers. Here I summarize the useful concepts from reliability engineering and their math relations.

Reliability engineering

λ = failure rate, expressed in failures per unit of time

MTBF (mean time between failures) = 1/λ // why? see hazard function and exponential distribution

AFR = 1 - e^(-exposure_time/MTBF) = 1-e^(-exposure_time*λ) = probability of failure occurs within the exposure_time

Assuming a small AFR (<5%), we can approximatedly have AFR ≈ 8760/MTBF

1 - AFR = probability of failure does not occur (survived) within the exposure_time

Hazard function

T = a random variable of the time until some event of interest happens

f(t) = probability density of event happens at t

F(t) = P(T<=t) = probability of event happens before t

S(t) = survivor function / reliability function := 1 − F(t) = probability of event happens after t, or say event survived beyond t

h(t) = hazard function := lim(h->0+, P[t ≤ T < t + h|T ≥ t]/h) = f(t)/S(t-) = - d ln(1-F(t)) / dt = - d ln(S(t)) / dt

h(t)dt = f(t)dt/S(t) ≈ P[fail in [t,t+dt) | survive until t]

H(t) = cumulative hazard function := ∫ (0->t, h(u)du) (t>0) = -ln(1-F(t)) = -ln(S(t))

So, S(t) = e^−H(t), f(t) = h(t)e^−H(t)

Exponential Distribution: T ~ Exp(λ), for t>0.

f(t) = λe^−λt for λ > 0 (scale parameter)

F(t) = 1 − e^−λt // this is the AFR mentioned above

S(t) = e^−λt // this is the (1 - AFR) mentioned above

h(t) = λ // constant hazard function. this is the failure rate mentioned above

H(t) = λt

Characteristics:

E(T) = 1/λ // this is the MTBF mentioned above

"Lack of Memory": P[T > t] = P[T > t + t0|T > t0]. Probability of surviving another t time units does not depend on how long you’ve lived so far.

Reference: [1]

Calculating MTBF from observation

observed AFR = failed device count / total device count

calculated MTBF(hrs) = 8760 / AFR // 8760 is the number of hours in a year

exposure_time: for storage system with auto repair, the exposure time of second node failure should be the recovery window

failure possibility in a given time window = F(t) = 1 − e^−λt ≈ λt = t/MTBF = t * AFR / 8760, t is the time window length. note that for storage systems, time unit of hour may be more appropriate

Availability vs durability

Availability: the probability of data is accessible by user. The data needs to be on disk, and server nodes have to be healthy. Also the network.

Durability: the probability of data is safe on disk. The data may not available to user, but still on disk.

For example: AWS S3 offers 99.999999999% durability and 99.9% availability.

Data loss probabilities

Basics

A(n, k) := Permutation(n, k) = n! / (n-k)!

C(n, k) := Combination(n, k) = n! / ((n-k)! k!)

Zm := {0, 1, .., m-1}

Subset(A) := {a | a is subset of A}

¬A := overbar A := complementary set of A

I := the complete set = A + ¬A

Code schema (D-K, K) := the simplest erasure-coding schema of D-K data fragments and K parity fragments. When lost fragment count <= K, survive. When lost fragment count > K, lost this extent.

P(event): a probability is operating on event. An event is a set. So set algebra applies to events.

∩: event1 AND. This is aligned with set algebra

∪: event1 OR. This is aligned with set algebra

¬ or overbar: event NOT happen. This is aligned with set algebra

Basic formulas (proof omitted)

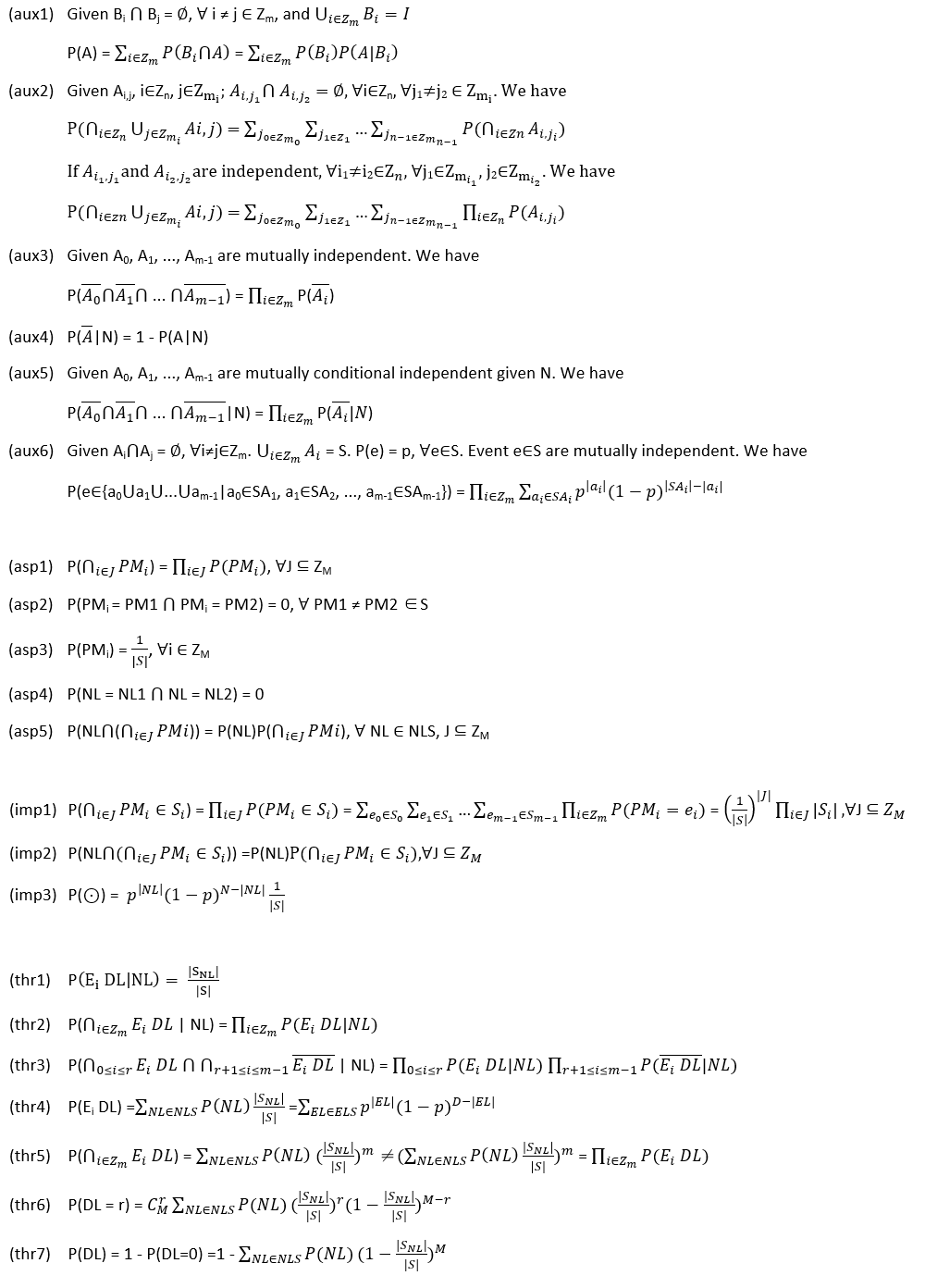

Event breakdown formula: (aux1)

Multiple event breakdown formula: (aux2)

If Ai are mutually independent, then ¬Ai are mutually independent: (aux3)

Conditional probability can reverse: (aux4)

If Ai are mutually conditional independent given N, then ¬Ai are mutually conditional independent given N: (aux5)

Space division, which is useful for node failure probability: (aux6)

Notations

Cluster setup:

We have N nodes, each have independent probability p to fail.

We have M extents (extent is the basic data unit, i.e. object), each is encoded into a D-fragment code.

We randomply place the fragments on nodes, each node holds at most 1 fragment from a given extent.

The code schema can be complex, e.g. LRC code.

The placement may have constraints, e.g. domains, copysets.

Node failure

Node set is ZN ("N" in subscript)

NL := a node failure event. NL is a subset of Zn.

NLS := the space of NL = Subset(Zn)

Extent and Extent Loss

Ei := Extent i, i in ZM ("M" in subscript)

EL := an extent loss event = {indexes of the lost fragments} // fragment index is element of ZD ("D" in subscipt)

ELS := the space of EL = {EL|any EL}, it is the set of which fragment-loss can cause extent loss

¬ELS := Subset(ZD) - ELS, it is the set of safe fragment-loss

Placement

PM := a placement = [node indexes of the placed fragment, for fragment from idx=0 to idx=D-1]

PMi := extent i's placement

Sall ("all" in subscript) := {all possible placements }

S := set of the allowed placements, S is subset of Sall, due to placement constraints

SNL ("NL" in subscript) := {placement that will cause extent loss}, given NL

∩h ("h" in subscript) := set intersect and map node index to fragment index. if (PM ∩h NL) is element of ELS, we have extent lost.

Data loss

Ei DL := an event of extent i is lost. P(Ei DL) is the probability of lost extent i

Ei DL | NL = extent i loses, given NL. P(Ei DL|NL) is the conditional probability of Ei DL given NL

DL := an event of data loss. P(DL) = P(DL>0) is the probability of losing at least 1 extent in the cluster. P(DL=r) is the probability of losing r extent in the cluster.

Assumptions

Extent placements are mutually independent: (asp1)

Given an extent, placements are exclusive: (asp2)

Placement is evenly randomized: (asp3)

Node failure is exclusive: (asp4)

Node failure is independent with extent placement: (asp5)

Implications (proof omitted)

Extent placement sets are independent: (imp1)

Node failure is independent with extent placement sets: (imp2)

Sample space (elementary event space)

An elementary event is: (NL, PM0, PM1, .., PMM-1) ("0", "1", .., "M-1" in subscript)

The sample space is: NLS × S × S × ... × S (count of S = M)

Given NL, P(ʘ) := elementary event probability, P(ʘ) formula: (imp3)

Key takeaway: most of the proofs below is conducted by breaking events down to elementary events

probability is essentially counting elementary events

Conclusions (proof omitted)

Calculate P(Ei DL|NL): (thr1)

(Ei DL|NL) are mutually conditional independent: (thr2)

(Ei DL|NL) and ¬(Ei DL|NL) are mutually conditional independent: (thr3)

Calculate P(Ei DL): (thr4) // To prove the two forms are equal, breakdown them into P(ʘ)

Ei DL are not independent: (thr5)

Alternative assumption, Ei DL are still not independent: Assume extent placements are fixed/known, the sample space becomes NLS. Find a counter-case: PMi, PMj are overlapped.

Data loss count distribution: (thr6)

Data loss probability: (thr7)

P(Ei DL) vs P(DL): connected by |SNL|/|S| ("NL" in subscript), but not always matched

Counter-case: from (N, p, D, K, M) = (20, 0.16, 4, 1, 50) to (20, 0.16, 12, 2, 50), P(DL) drops, but P(Ei DL) raises.

P(Ei DL) vs P(DL): meaning

P(Ei DL): when a customer asks how easy is his extent to be lost.

P(DL): when the operation asks how easy will they encouter data loss alert, and how much lost data.

Questions

If we have a large number of nodes, and many extents, will the extent loss event become nearly independent?

We can think this way

Since cluster is large, (Ei DL) is less affected by (Ej DL).

When we take extents E0, E1, ..., Em-1, they are more likely to be not overlapped

When E0, E1, ..., Em-1 are not overlapped, we can deduce that Ei DL are independent

Below are the formulas stated above

Reliability Limits

I want to explore what limits the reliability of super large storage clusters.

Basics

E(a) := expectation of random_variable

E(a|case) := conditional expectation of random_varable = sum(v in {a's possible values}, v*P(a=v|case))

Basic formulas

Conditional expection: (aux7)

Notations

λ := node failure rate = d(P(node fail in time dt))/dt = a constant

dt := a very small time window, which is usually used with λ

λdt = node failure possibility in time window dt

K := K that, an extent losing l>K fragments is never recoverable, losing l<=K fragments can be recoverable

usually, K = parity fragment count

SR := storage overhead = D/(D-K)

SD := user data size per extent

TD := total user data size

DS := fragment size = SD*SR/D = SD/(D-K)

Assumptions

Breakdown extents by how many fragments lost: (asp6)

Ml ("l" in subscription) := extent count of losing l fragments

NB := network bandwidth for data recovery. note that other network bandwidth can be used for customer traffic

NBl ("l" in subscription) := network bandwidth for recover extents in Ml

rvl ("l" in subscription) := given the code schema, in all cases of losing l fragments, ratio of the recoverable

Conclusions

First, we study the the stable state. I.e. NBl needs to be proper to hold Ml stable.

Extent count that flows into Mi due to node loss: (thr8)

Extent count that flows into Mi due to recovery: (thr9)

Extent count that flows out of Mi due to recovery: (thr10)

Extnet count that flows out of Mi due to node loss: (thr11)

By balancing the flow in and flow out, to maintain the stable state, we have: (thr12). Conclusions

It is not possible to balance. Not possible even M0=K, M1..MK = 0. There is no balance state.

If we force M0..MK-1 to balance, MK will drop. The process repeat until all MK..M1 drop to 0, surviving extents retract to M0

If we force MK..M1 to balance, M0 will drop. The process repeats until all M0..MK-1 drop to 0, surviving extents retract to MK

A healthy cluster can only be M0=M: (thr13)

The other M1..MK should be infinitely small, ignorable count

Next, lets find out data loss rates

Extent loss rate λ(ext): (thr14)

Cluster data loss rate λ(DL): (thr15)

λ(ext) and λ(DL) are the solo result of Mi states. They has not relation with NBi. While NBi is what maintains Mi states.

When M0=M, λ(ext) and λ(DL) are the best of what they can get from NBi.

Practical markov for single extent loss probability: (thr16)

Notations

Let NBSi := the available network recovery bandwidth for this single extent, when it has lost i fragments

The bandwidth is affacted by repair priority, TOR and node NIC bandwidth.

P(EDL Mi) := probability of lose this extent when it is at Mi

P(EDL M0) is what we try to calculate

Note that this formula not math strict, because in a absorbing markov chain the extent loss probability should be eventually 1

https://www.dartmouth.edu/~chance/teaching_aids/books_articles/probability_book/Chapter11.pdf

But we are here to calculate the "practical" probability

This formula assumes we follow the repair lifecycle of the given extent

While the above λ(ext) assumes we take any extent from the cluster, which has M1-MK count is infinitely small

This formula is useful because

It takes network recovery bandwidth into consideration, very practical

It follows the entire repair lifecycle of the given extent

Conclusions

To maintain cluster healthy, recovery bandwidth NB shoud be no less than λ*TD*SR.

The necessary recovery bandwidth growth with total user data size, code schema storage overhead, but not cluster node count.

Recovery bandwidth NB limits how much data can be there in a super large storage cluster

λ and code schema storage overhead multiply it by factors

Cluster node count has no relation with NB. But user data size does.

For customer-faced reliability, extent loss rate λ(ext) should be low. It is the direct result λ and code schema

For operation ease, cluster data loss λ(DL) should be low. It is the direct result of λ and code schema.

λ(ext) and λ(DL) have no direct relation ship with NB. But NB is necessary to pull extents from M1..MK != 0 states.

If M1..MK != 0, the λ(ext)dt and λ(DL)dt raise by factor of 1/(λdt)

Below are the formulas stated above

Reliability framework

To summarize the technique framework to ensure storage reliability

* Data input: ensure the reliability when data is coming in

* End-to-end verification: ensure what user writes is what is stored

* Commit safe: when user is ack-ed, ensure the data is guaranteed persistent

* Data storing: ensure the reliability at where data is stored

* Good data should not be overwriten. In case a bug or at least we can recover data from history

* Data recovery

* Detect data loss as fast as you can

* On-the-fly, when user read data, from node loss, from disk failure, etc. Summarize whatever info you can leverage to detect data loss fast.

* Prediction, from unstable/unhealthy/untrustable nodes that are going to loss, from disks that frequently have problem. Prepare to move data out of danger zones.

* Repair action should be prioritized

* Repair the data at high risk first.

* Repair actions should be well-scheduled and well-managed.

* The overall reliability is determined by how fast you can repair.

* Watch out that your data is more vulnerable when server upgrading, because

* Some portion of data is unavailable

* The user traffic becomes larger because of reconstruction read

* The repair traffic also becomes larger

* Code schema (e.g. 3-replica, erasure-coding, LRC) is very important for data reliability.

* It is also important for balancing reliability with overhead of storage, bandwidth, latency, reconstruct, and metadata.

* Policied auto transition between different code schemas may be necessary.

* Silent data corruption: This is a real problem. Background check and repair can help; but too time/resource consuming for super large clusters.

* Some piece hardware from vendors can have problem. Some firmware can have problem, go wrong, or have bug. They can become slow, unstable, or whatever.

* Old clusters are highly risked: old devices are easy to fail, and in burst, which generates a lot of data loss. They may frequently become slow, unstable, jump online and offline.

* Data serving

* Data availability and data durability are different. Good data serving ensures data availability

* Nodes can be transiently unavailable. Detect transient and permanent before you head to expensive data repair.

* Node failure can usually be repaired quickly by a reboot. Node can jump online and offline. Be careful to schedule repair actions wisely.

* Customer impact is different, i.e. even data is lost, if we are in the lucky time window where customer is not reading/writing (this is of high probabilty), there can be no customer impact.

* Raw disk recovery: when everything is goine, we expect to extract user data from a raw disk

* Make sure you have a way to know the raw binary format on disk. Extract data from raw disk can be the final resort.

* Make sure the necessary metadata for raw disk recovery can be obtained and well protected.

* Hardware: hardware failure rate has direct impact on everything about reliability, very straightforward. Be careful to balance reliability and cost wisely.

Other references

Create an Issue or comment below