Linearizability vs Serializability, and Distributed Transactions

Linearizability vs Serializability are basic concepts in distributed storage systems. However, they are easy to confuse. And there are few good materials to clarify them.

Basic concepts

Linearizability

Linearizability (also known as atomic consistency, strong consistency, immediate consistency) describes reads and writes on a single object (stores a single value). it doesn’t involve multiple objects. It doesn’t involve “transaction”, which groups multiple objects. It treats each operation as an atom, i.e. to take effect in a single time point, rather than a timespan.

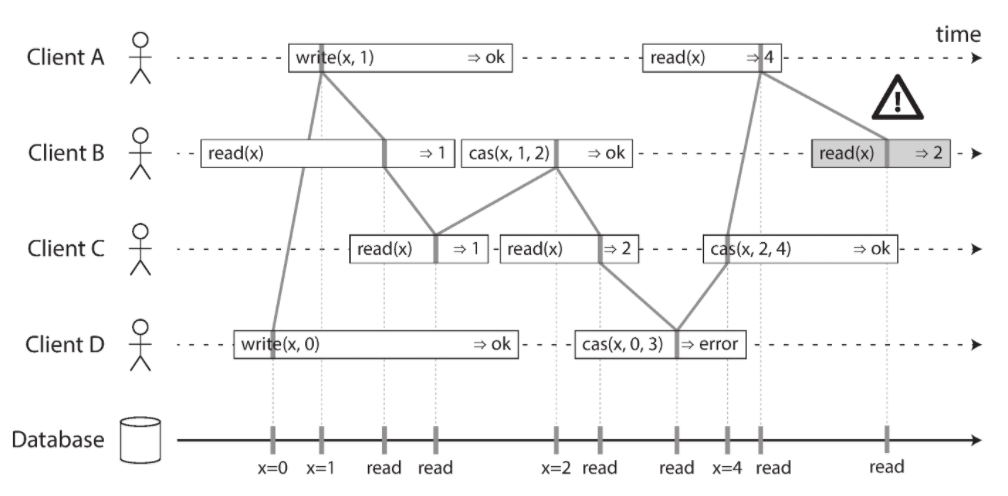

(Chart from Designing Data-Intensive Applications - Page 328)

(Chart from Designing Data-Intensive Applications - Page 328)

Linearizability supports two operations: read a value, write a value. It can be more useful (we’ll see later) if compare-and-set is also supported.

Linearizability is a recency guarantee. Once a writer sets new value, the value immediately takes effect. All readers immediately see the new value. Readers always read the newest value. Operations in Linearizability are by nature total ordered, and there are no concurrent operations.

Serializability

Serializability is an isolation level for database transactions. It comes from database community area, where is a different area that Linearizability originates.

Serializability describes multiple transactions, where a transaction is usually composed of multiple operations on multiple objects.

Database can executed transactions in parallel (and the operations in parallel). Serializability guarantees the result is the same with, as if the transactions were executed one by one. i.e. to behave like executed in a serial order.

Serializability doesn’t guarantee the resulting serial order respects recency. I.e. the serial order can be different from the order in which transactions were actually executed. E.g. Tx1 begins earlier than Tx2, but the result behaves as if Tx2 executed before Tx1. That is also to say, to satisfy the same Serializability, there can be more than one possible execution schedulings.

Realworld databases

Serializability with transaction timestamps

In databases, Serializability is usually reflected by transaction timestamps. Transactions, though executed in parallel, behave like they executed in the serial order of their timestamps.

Serializability requires the total order of transactions. The transaction performs its reads and writes at the same timestamp (its commit timestamp). However in Snapshot Isolation, a transaction’s read and write timestamps are allowed to drift apart. (Stated in Cockroach paper - 3.3, or this article.)

Linearizability with transactions

Modern databases usually equipt with MVCC and snapshot isolation. Reads target on a certain version, rather than the latest value. Remember Linearizability always reads the latest value; i.e. recency. As a result, Linearizability becomes a less useful concept for transactions.

But “recency” is still a useful ingredient. Spanner coined the concept External Consistency. It combines “recency” into Serializability (though Spanner paper directly calls it “linearizability”).

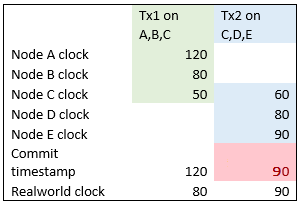

Remember Serializability allows a serial order that an earlier Tx1 behaves as if executed later than Tx2. It is the violating case that External Consistency wants to capture. See below chart. Nodes have inconsistent clocks. Tx1 executed earlier than Tx2. But Tx1 obtained a later (bigger) commit timestamp. Particularly on Node C, Tx2 sets value later than Tx1, but Tx2 is setting with an earlier (smaller) timestamp. This is abnormal.

Spanner fixed the above issue with Commit Wait. You can read more at article1, article2.

Linearizability with quorum read

Dynamo-style quorum write/read is a smart way to implement “strongly” consistency.

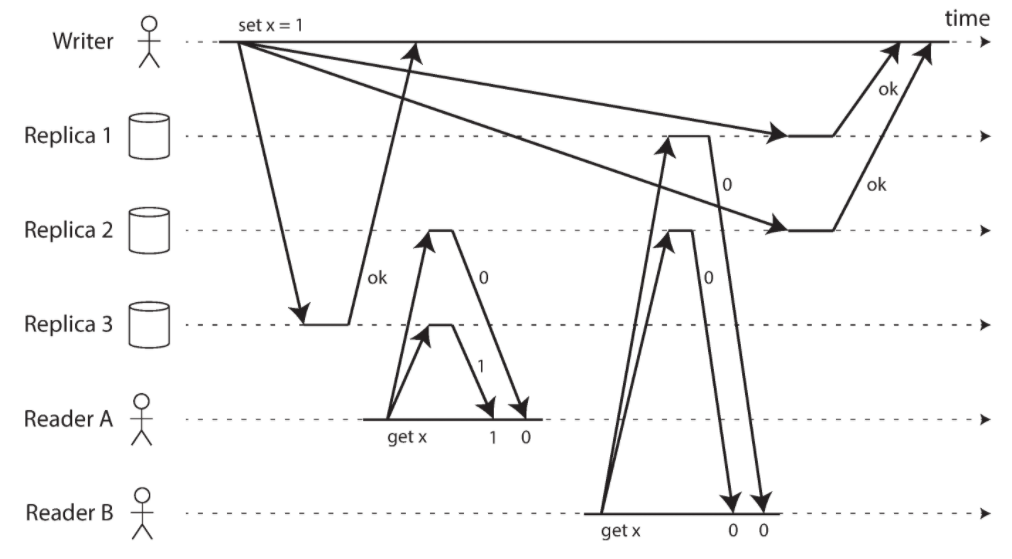

However, see below chart (N=3, W=3, R=2). Network has varying delays. Client A sees partially the new value 1, but client B sees only the old value 0. Linearizability is (partially) violated.

(Chart from Designing Data-Intensive Applications - Page 334)

(Chart from Designing Data-Intensive Applications - Page 334)

Things can become more complicated when Replica nodes have varying clocks and concurrent writes.

Total Order Broadcast and Consensus

Total Order Broadcast and Consensus are closely related concepts with Linearizability. And we will later see Linearizability with compare-and-set <=> Total Order Broadcast <=> Consensus; they are equivalent.

Total Order Broadcast

Total Order Broadcast (also known as atomic broadcast) is a protocol to exchange messages across nodes. It satisfies

-

Reliable delivery: If a message is delivered to one node, it is eventually delivered to all nodes. If one node receives the message, then all nodes eventually receive the message. Or on the contrary, no node receive the message. You can see the atomicity of all or nothing here. And message delivery is not required to happen immediately.

-

Total ordered delivery: If a node receives Msg1 first and then Msg2, any other node must also receive Msg1 first and Msg2 second. Messages delivered are totally ordered. And each node receives messages in the same order. More, the order is fixed, where no node is allowed to insert a message into an earlier position.

-

Uniform Integrity: A message is received by each node at most once, and only if it was previously broadcast. (This property is mentioned in Wiki but somehow missed in the Designing Data-Intensive Applications book, page 348.)

You can find that Total Order Broadcast behaves eactly like a log that is consensus across all nodes. Messages are ordered by LSN (log sequence number). CORFU is a realworld project that builds the distributed shared log.

Consensus

Consensus is usually described as multiple nodes proposing values, and nodes eventually agree on the same proposed value. A consensus algorithm satisfies:

-

Uniform agreement: Every node eventually agrees on the same value.

-

Integrity: If a node decided value v, it must always decide the same value in future.

-

Termination: Every node (that didn’t crash) eventually decides some value.

The best known consensus algorithms are Viewstamped Replication (VSR), Paxos, Raft, and Zab (ZooKeeper)

Total Order Broadcast can be seen as many rounds of consensus. In each round, nodes propose the message to send next, and then decide and agree on the next message to be delivered in total order. Also, Paxos implementation usually relies on the the underlying logs. The log can be seen as the broadcast messages ordered across all nodes.

Though 2PC (Two-phase commit) is a popular algorithm, it does not satisfy the “Termination” property. A typical mitigation is to implement each participant and coordinator as a Paxos quorum, which is highly available. See Spanner.

Equivalence to Linearizability

From the above, you can see Consensus and Total Order Broadcast are equivalent. I.e. we can use one to implement the other. E.g. Paxos is essentually broadcasting ordered log messages. Total Order Broadcast, in each message round, can use Paxos to agree on message broadcast order and message exactly once.

More, both Total Order Broadcast and Consensus are equivalent with Linearizability.

-

Linearizability can be implemented with Total Order Broadcast. Imagine the shared log. Writes are inserted into the log, broadcast to all nodes in the same order. Reads never disagree on different history. To ensure recency of reads, we can insert the read into the log too, where the LSN is the point-in-time when read is performed (this is how to implement Linearizable Quorum Reads in Paxos). Alternatively, to ensure recency of reads, we can invoke sync() before read, to make sure nodes are update; or we just use synchronous message replication. Linearizable compare-and-set is obvious to implement because reads always see the same value on every node.

-

Total Order Broadcast can be implement by Linearizability with compare-and-set. Suppose every message has an incrementing LSN. Upon a new message arrival, the node compare-and-sets the last LSN+1 with the new message’s LSN. So that only the next message (LSN+1) can be accepted. In this way, every node receives every message in the same total order. Messages can be resent. By verifying the LSN, the nodes lagging behind can receive the next message, and a duplicated message can be detected and dropped.

-

Linearizability can be implemented by Consensus. This is essentially the same way as Linearizability to be implemented by Total Order Broadcast. Consensus can be implemented by Linearizability. Recency is essentially every node to have reached consensus on the new value written.

More things equivalent

Besides the equivalence chain, Linearizability with compare-and-set <=> Total Order Broadcast <=> Consensus, there are more things equivalent to them. These equivalence are among the most profound and surprising insights into distributed systems. (Designing Data-Intensive Applications book, page 374.)

Distributed Locks

-

Distributed Locks can be implemented by Consensus. Lock requires Linearizability: every node must agree on who owns the lock. This is what Consensus guarantees. Besides, distributed lock is usually implemented as a Lease, which can be expired upon lock owner crash.

-

Consensus can be implemented by Distributed Locks. The node owning the lock is the Leader. Followers simply agree on whatever the Leader says. Leader selection is a useful service provided by etcd or ZooKeeper, to shift the burden of implementing the complexity of Paxos.

Uniqueness Constraint

-

Uniqueness Constraint can be implemented by Distributed Locks. A typical use case of Uniqueness Constraint is to avoid creating duplicated usernames. Obviously, just lock the write to the object to be unique. Or, Linearizability compare-and-set can also be used to implement Uniqueness Constraint.

-

Distributed Locks can be implemented by Uniqueness Constraint. Locking is the unique ownership of the lock object. Uniqueness Constraint ensures the owner is unique.

Atomic Transaction Commit

-

Distributed transaction can be implemented by a shared log which is consensus across all nodes. The shared log is the Total Order Broadcast. Atomic Transaction Commit means every node in the end agrees on the same whether to commit or abort the distributed transaction, i.e. a consensus.

-

Total Order Broadcast can be implemented by distributed transaction. Each message round maps to a transaction commit. Distributed transaction is a more capable semantics, where it can carry anything you need. An Atomic Transaction Commit maps to a message accepted in Total Order Broadcast.

These equivalence forms the foundation that we can implement distributed transactions. We will see more in the next section.

Into the distributed transactions

Modern databases usually distribute partitions across multiple nodes, or even geo-regions. The distributed transactions, which coordinate across multiple partitions, are challenging. Typical industry implementations all template (verb) from 2PC: Percolator, Spanner, CockroachDB, TiDB.

The liveness issue of 2PC is mitigated by running each 2PC participants (table partitions) as a Paxos quorum, which is highly available. The coordinator can run on one of the participant quorum to achieve high availability (Spanner), or coordinator failure results in transaction abort (CockroachDB), or the coordinator runs on a separated highly available service (TiDB).

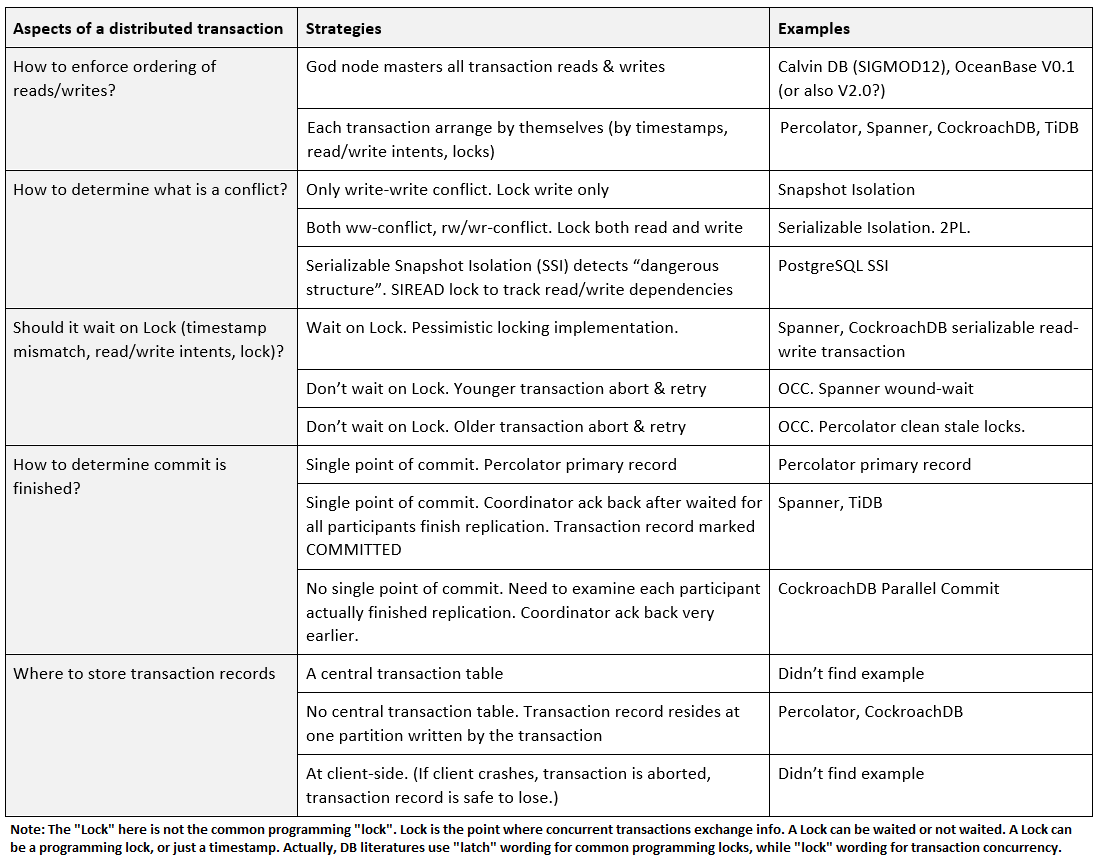

2PC can be much more flexible .. actually .. Let’s think about a series of questions.

First, how do transaction operations (reads, writes) enforce their ordering?

-

Method 1, God node: A god node, which knows every transaction, uniformly schedules each operation for every transaction, to reach the desired isolation level. Partition nodes blindly execute the scheduled operations, requiring no coordination. The god node can be replicated or backup using Paxos, to achieve high availability. Probably, the god node can also scale-out by partitioning, if the transactions are absolutely non-overlapping. The distributed transaction problem is then reduced to single node transaction, and the algorithm is not 2PC. Realworld systems include OceanBase V0.1 (or also V2.0?) and Calvin DB.

-

Method 2, discentralized: There is no central god. Each transaction arranges operations by themselves. They leverage timestamps, read/write intents, or locks. Here I generally call all of them Locks. It simplifies later discussion. Because Lock here is the general thing that a transaction gets aware of other transactions, and determines either to wait or abort/retry. And transaction implementation usually combines locking and writing staging data into one step, i.e. you get write intent. 2PC works in Method 2.

Next, how do transactions determine conflicts? What is treated as a conflict?

-

Lock write only: Only overlapping write sets are treated as conflict. Read is never blocking nor requiring a lock. This is typically how snapshot isolation is implemented. Though snapshot isolation suffers from Write Skew problem, because without locking read set, the transaction doesn’t know its premise has changed. Databases with Serializability isolation level may also offer “Snapshot Read”, which doesn’t require locking.

-

Lock both read and write: This is typically how Serializability isolation level is implemented. The mechanism is also known as 2PL (Two-phase locking. Note it’s irrelevant with 2PC, see here). Lock everything, you are perfectly safe, but bad performance. The locking can be made more fine-grain with Predicate Locks or Index-range Locks.

-

Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI): This is a newer approach, implemented in PostgreSQL. SSI tracks read/write dependencies in transaction. Before a transaction commits, it checks whether isolation level is violated. E.g. another Tx committed; by tracing back the read/write dependency, we find the read/write set of the victim transaction is changed, then we know the victim transaction needs to abort and retry. Transaction execution is non-blocking. Though the algorithm requires transaction to acquire “SIREAD lock”, which tracks read/write dependency. (So you see “Lock” doesn’t necessarily mean blocking. It’s just wording.)

-

Serial Safe Net (SSN): Paper, Slides, Review here. SI+SSN is the common way to achieve Serializability. SSN is similar with SSI that it rejects committing transactions potentially can compose dependency loop. SSN provides improvements compared to SSI that it rejects less false positives and offer higher concurrency. AWS Redshift made more improvements to SSN by evaluating certification earlier to reduce CPU/memory consumption.

The Lock mentioned above is generalized. It can be the common literature lock (e.g. MySQL InnoDB), or a read/write intent (e.g. CockroachDB), or just a timestamp (e.g. Percolator), or a read/write dependency tracker (the SSI algorithm). Instead of calling them Lock, they are actually the “share points” between transactions. Transactions use these “share points” to interact with each other, and to determine the ordering of their read write operations.

(More complications .. If you are thinking if Lock is implemented by timestamp, how can the code atomically compare the timestamp and commit, or to implement the blocking behavior. First, see Latches vs Locks. The Latch vs Lock difference comes from database community area, where Lock applies to transaction and Latch applies to database internal code, where they are both to control the concurrency. In the typical code, cmtlock.Lock(); compare timestamp; do commit; cmtlock.Unlock(), cmtLock is a Latch, while the Lock here is timestamp, or you can even say it’s a lockless OCC transaction protocol (which uses Latches). So to answer the initial question, in database internal code, the atomic condition check & do and blocking behavior can be implemented by Latches. Besides, B-tree is also a place to use many Latches.)

Next, when a transaction encounters the Lock held by another Tx, should it wait or not?

-

Should wait on Lock: You get the typical pessimistic locking implementation, e.g. snapshot isolation (Lock write only), or serializable isolation (2PL).

-

Don’t wait on Lock, younger transaction retry: If don’t wait on Lock, one of the two racing transactions must abort and retry (or more cleverly, “half retry”, e.g. “Read Refreshes” in CockroachDB); otherwise the isolation level is violated. This typically results in OCC (Optimistic Concurrency Control) locking implementation. Take as an example the snapshot isolation upon write-write conflict. The commit timestamp on the overlapped write set can be seen as the generalized Lock. When the older transaction commits, the timestamp is advanced. Later when the younger transaction sees the timestamp is higher than what it remembers, it knows write set was changed in middle; the younger transaction then aborts and retries. (This paper illustrates MVOCC.) Spanner wound-wait is another example. The “older” transaction will “wound” (abort) the younger transaction holding a lock, when the lock is requested by the older transaction.

-

Don’t wait on Lock, older transaction retry: The example is Percolator. You can see read operation (

Get(c)) will cleanup the locks held by on-going write transactions (cleanupStaleLock(k, ts)). These on-going write transactions are the “older” transactions here. They are aborted because lock is cleaned up, by the reads from younger transactions. You can find it’s very aggressive to always let younger transactions to abort older transactions. Actually in Percolator paper,BackoffAndMaybeCleanupLockhas more details. The younger transactions will use a Chubby token to determine whether the older transaction is still alive, before proceed aborting it.

Actual database may combine multiple wait / no-wait strategies. E.g. In Spanner wound-wait, the younger transaction chooses to block wait for the lock holder (the older transaction), while the older transaction immediately aborts the lock holder (the younger transaction). E.g. CockroachDB handling write-write conflicts also combines wait older abort younger behavior. E.g. TiDB implements both Optimistic and Pessimistic versions of Percolator algorithm.

Next, how do a distributed transaction determine the commit is finished? We know the information is scattered on many nodes.

-

Single point of commit: Percolator selects a primary record among all the records to be written by the transaction. Though all records acquire lock, the lock at primary record acts as the single point of synchronization: 1) Each secondary record lock points to the primary record. 2) If the primary record is locked, the transaction can commit without examining locks on any secondary record. 3) If the primary record is committed, the whole transactions is seen as committed; while secondary record write intents can be applied async (by next readers). 4) When someone tries to abort the transaction, it cleans the primary record lock first, which immediately aborts the whole transaction. BigTable only provides record-level (i.e. row-level) compare-and-set (atomic ReadModifyWriteRow). The smart part is, with the primary record as the single point of commit, Percolator can examine primary record lock (stored in the same primary record row) and commit write intent (add a pointer in the primary record row to point to the write intent) within one record-level compare-and-set.

-

Coordinator waits for all 2PC participants to finish replication: Remember Spanner, CockroachDB, TiDB use 2PC for distributed transaction. Each participant replicates on Paxos quorum to achieve high availability. For a transaction to finish the commit, it sends requests to each participant and wait for the quorum to finish replication. The single point of commit is coordinator ack back, or transaction record marked COMMITTED. You may notice when two racing Tx1 and Tx2 are sending write intents (i.e. locks) to the same set of participants, if the order of locking is interleved, Tx1 and Tx2 can deadlock. Spanner uses wound-wait to avoid deadlock. CockroachDB employs distributed deadlock detection to abort cycle of waiters.

-

Each 2PC participant actually finished replication async: This is the Parallel Commit used in CockroachDB. An OceanBase article also mentioned the similar idea at year 2016. Similar with “.. Wait for all 2PC participants ..”, transaction coordinator sends requests to each participant. Differently, the coordinator then immediately ack back to user client saying commit finish (STAGING state). Now the transaction may eventually success (COMMITTED state) or abort, depends on whether “Each 2PC participant actually finished replication” in their quorum. The result is async. There is NO single point of commit. Following transactions need to run an evaluation phase (called “Transaction Status Recovery Procedure”), polling each participant, to determine whether the former transaction truly finished replication (i.e. successfully committed). To avoid the costly evaluation phase, coordinator also aggressively evaluate and move former transaction to COMMITTED state. Note, Parallel Commit also avoids coordinator failure to block 2PC, because commit finish condition is now shifted to participants.

The last question is, how should we store transaction records in a distributed database? A transaction has states to save, e.g. COMMITTED, PENDING, ABORTED, and also other metadata. It’s usually called the transaction record.

-

A central transaction table: Database may use a central transaction table to store all transaction records. This simplifies things by separating metadata management from transaction processing. The central transaction table can be made highly available by Paxos replication, and scale-out by partitioning. It can be just another plain table, to leverage the partitioning and replication already provided by the distributed database.

-

No central transaction table: Distributed database favors distributing everything. Percolator uses the primary record as the single point of commit. It doesn’t even need a transaction record. CockroachDB puts transaction record at the same partition of the first key in the transaction. All write intents point back to this transaction record.

-

At client-side: The transaction state may be tracked at user clients. It’s not highly available. The underlying assumption is, if client crashes, the transaction is aborted anyway, so we don’t need the transaction state any more neither.

TL;DR. I summarized all the above in a chart. The spectrum of strategies greatly helps understanding and designing distributed transactions. Given the spectrum, there are a few interesting possibilities seem missed to be addressed in any current implementation

-

Both 2PC and Paxos can be used to reach Consensus. Distributed transactions currently use 2PC to commit (while Paxos is only for high availability of table partition). Can instead Paxos be used to commit a transaction? E.g. coordinator only needs to send commit requests to at least N/2+1 participants, rather than all, which relieves tail latency. E.g. writes to partition A can be temporarily buffered at partition B first, if A shows high latency.

-

God node greatly simplifies the complexity of distributed transactions. It should also have performance advantage because of less cross-node interactions. Can God node be scaled out by partitioning? It should be feasible given we know for sure that two transactions will never overlap.

Create an Issue or comment below